Understanding U.S. State Taxes: A Complete Guide

When discussing taxation in the United States, many focus on federal taxes. However, US state taxes form a major part of the overall tax responsibility for individuals and businesses. Each of the 50 states, along with Washington D.C., operates under its own tax system with unique rates, tax types, and compliance rules. A thorough understanding of state taxes is essential for effective financial planning and compliance.

What Are State Taxes?

State taxes are levied by individual states on income, sales, property, and other financial activities within their jurisdiction. Unlike federal taxes, which are consistent across the country, state taxes reflect local economic conditions, political choices, and funding priorities. These revenues fund essential services such as public education, healthcare, infrastructure, and safety.

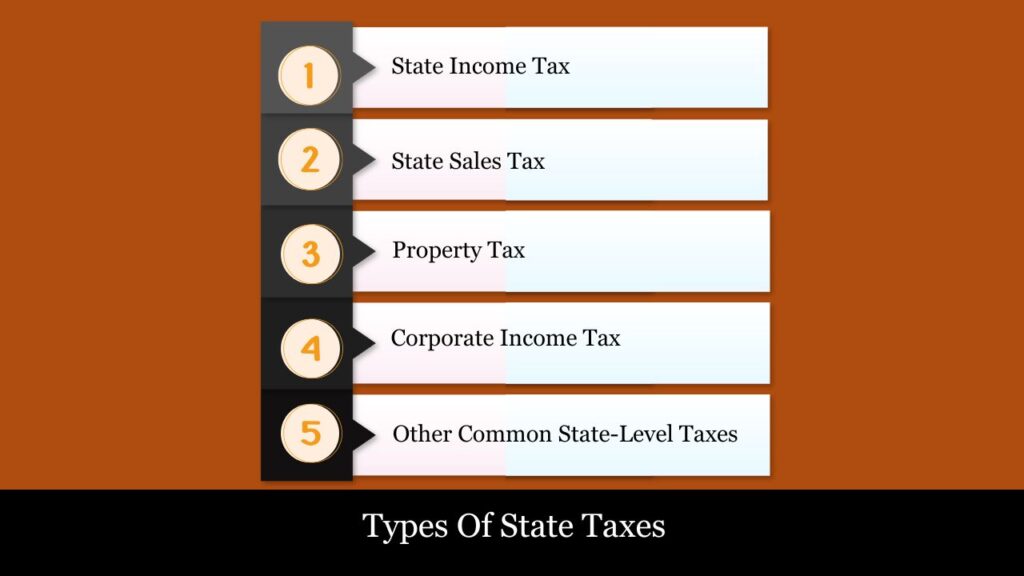

Types of State Taxes

State Income Tax

- Progressive Rate Systems: Many states impose a tiered tax system where higher income brackets are taxed at higher percentages. States like California and New York are notable for their steep progressive tax rates.

- Flat-Rate Systems: Some states apply a consistent tax rate to all income levels regardless of earnings (e.g., Colorado at 4.4%, Illinois at 4.95%).

- No Income Tax: Nine states, including Florida, Texas, and Washington, do not impose any personal income tax on wages or salaries.

State Sales Tax

- Levied on most goods and services at the point of sale.

- States may allow additional local sales taxes, making combined rates higher in some areas.

- Exemptions and reduced rates may apply for necessities like groceries, clothing, or prescription medications.

Property Tax

- Primarily collected by local authorities (county, city, school districts), but regulated and utilized at the state level.

- Based on the assessed value of real property, and in some states, tangible personal property like vehicles.

Corporate Income Tax

- Imposed on the net income of corporations doing business within the state.

- Rates and apportionment formulas vary widely by state, ranging from 0% to over 12%.

Other Common State-Level Taxes

- Excise Taxes: Targeted on specific goods such as alcohol, gasoline, tobacco, and cannabis.

- Estate and Inheritance Taxes: Collected by certain states on the transfer of assets upon death.

- Unemployment Insurance (UI) Taxes: Required from employers to fund state unemployment benefit systems.

- Registration & Licensing Fees: Applied to motor vehicles, professionals, and certain business activities.

How State Taxes Affect You?

State taxes can have a substantial influence on your overall financial situation, from the amount of tax you owe each year to how you manage your investments and choose where to live or work. Understanding their impact is key to efficient financial planning.

- Residency and Source of Income: Your state of residency largely determines your income tax obligations. If you live and work in the same state, you’ll file a single return. However, if you work across state lines or move mid-year, you may have to file in multiple states. Some states offer credits for taxes paid to other states, helping to prevent double taxation.

- Impact on Take-Home Pay: States with high income taxes reduce your net earnings more significantly than those with lower or no income tax. For example, a professional earning $100,000 annually in California will retain less after taxes than someone earning the same amount in Florida, which levies no income tax.

- Business and Investment Decisions: Entrepreneurs and corporations must consider state corporate taxes, sales taxes, and regulations. Business-friendly states like Texas and Nevada attract companies due to low or no income taxes. Investors also consider state capital gains and estate tax laws when managing assets.

- Property Ownership and Cost of Living: High property taxes (common in states like New Jersey and Illinois) can significantly impact homeownership affordability. Combined with sales and income taxes, property taxes influence overall living expenses in each state.

- Retirement and Relocation Planning: Retirees often weigh state tax burdens—including taxation on retirement income, pensions, and Social Security—when deciding where to settle. States like Florida, Tennessee, and Nevada are favored for their tax-friendly retirement environments.

- Access to Public Services: While low-tax states offer immediate savings, they may spend less per capita on education, healthcare, or infrastructure. The level of services available can vary significantly depending on a state’s tax base and priorities.

Factors Shaping State Tax Policies

State tax policies are not arbitrary—they are shaped by a combination of demographic, economic, political, and fiscal considerations. Understanding these influences can help taxpayers anticipate changes and better plan their finances.

- Economic Structure and Industry Base: States with robust industries such as finance, technology, energy, or tourism often have broader revenue streams. For instance, states like Texas benefit from oil revenues and sales tax, while California leverages income tax from its large entertainment and tech sectors. States with fewer industries may rely more heavily on sales or property taxes.

- Population Demographics and Urbanization: States with larger or more urban populations may require higher tax revenues to support infrastructure, education, and public safety. Conversely, rural states may adopt different tax structures to meet smaller-scale needs.

- Political Philosophy and Fiscal Approach: States with more progressive leadership may favour higher income taxes and robust social programs, while conservative states may prioritize low taxes and limited government intervention. This ideological divide strongly influences tax brackets, corporate rates, and available credits.

- Budgetary Needs and Fiscal Health: Each state’s budget and long-term debt obligations influence tax decisions. States with pension shortfalls or aging infrastructure may increase taxes to meet funding needs, while states with budget surpluses may offer tax relief or rebates.

- Tax Competitiveness and Business Climate: To attract businesses and residents, states often adjust their tax policies. Some may lower corporate income taxes or offer business incentives, while others avoid income taxes altogether to compete economically.

- Voter Influence and Ballot Initiatives: In many states, tax policy changes are subject to public referenda. Voter-approved caps on property tax rates or mandatory supermajority rules for tax increases can shape long-term tax strategies.

U.S. State Income Tax Rates & Compliance Overview

Understanding how state income tax systems operate is critical for ensuring tax compliance and optimizing financial planning. Unlike the federal tax system, which applies uniformly across the country, state income taxes vary widely in terms of rates, structures, exemptions, and filing protocols. This section offers an expanded and detailed look at state income tax rates, compliance rules, deadlines, and taxpayer obligations in the United States.

Overview of State Income Tax Systems

Out of the 50 U.S. states, 41 (along with Washington, D.C.) impose a personal income tax. Each state’s tax code is unique, shaped by political priorities, fiscal needs, and local economic conditions. These tax systems fall broadly into three categories:

- Progressive Income Tax States: Tax rates increase with income. High earners pay a higher percentage of their income compared to those with lower earnings.

- Examples: California (up to 13.3%), New York (up to 10.9%), and New Jersey (up to 10.75%).

- Flat Income Tax States: A single tax rate applies regardless of income level, offering simplicity and predictability.

- Examples: Colorado (4.4%), Illinois (4.95%), Indiana (3.15%).

- No Personal Income Tax States: These states rely on other forms of revenue, such as sales tax, excise tax, and property taxes.

- Examples: Florida, Texas, Washington, South Dakota, Wyoming, Nevada, and Alaska.

Detailed State Income Tax Rate Examples (2025)

| State | Tax Structure | Top Marginal Rate | Notable Features |

| California | Progressive | 13.3% | Highest top rate; surtaxes on high-income earners |

| New York | Progressive | 10.9% | Additional NYC tax may apply for residents |

| Illinois | Flat | 4.95% | Flat rate applies to all income levels |

| Colorado | Flat | 4.4% | Simple compliance; same rate for all taxpayers |

| Texas | No income tax | 0% | No tax on wages; relies heavily on sales/property taxes |

| Florida | No income tax | 0% | Popular with retirees; has intangible tax on investments |

Note: These rates may be updated annually. Always verify with your state’s Department of Revenue.

Residency and Filing Requirements

Your filing obligations depend on your residency status and income sources. States typically classify taxpayers into:

- Residents: Taxed on all income, regardless of where it is earned.

- Part-Year Residents: Taxed only on income earned during the time they lived in the state.

- Nonresidents: Taxed only on income sourced to that state (e.g., wages, rental income).

State Filing Deadlines

While most states follow the federal filing deadline of April 15, a few have different due dates:

| State | Deadline | Notes |

| Most States | April 15 | Matches federal deadline |

| Michigan | April 30 | One of the few with a later filing deadline |

| North Carolina | May 15 | Offers extended time to file |

| Massachusetts | April 17 | Adjusted for Patriots’ Day holiday |

Late filing can result in penalties and interest even if you are owed a refund.

How to Calculate & File State Income Taxes?: A Step-by-Step Guide

Filing your state income tax return is an essential part of staying compliant with tax laws. While federal tax rules are uniform across the U.S., state tax systems vary widely in terms of rates, deductions, forms, and deadlines. Below is a comprehensive, easy-to-follow guide to help individuals and businesses accurately calculate and file state income taxes.

Step 1: Determine Your State Residency Status

Your residency status determines which state’s income taxes you owe and how much.

- Resident: You live in the state for most or all of the year and must report your worldwide income.

- Part-Year Resident: You moved in or out of the state during the tax year. You only pay taxes on income earned while a resident.

- Nonresident: You do not live in the state but earned income from sources within it (e.g., job, rental, business).

Why it matters: Each status has different filing requirements and affects your eligibility for deductions or tax credits.

Step 2: Collect Required Income and Tax Documents

To prepare your state return, gather all relevant financial and tax documents:

- W-2s (wages from employment)

- 1099s (freelance, interest, dividend, or investment income)

- K-1s (partnerships or S corporation distributions)

- Schedule C or Schedule E (for self-employment or rental income)

- Federal Tax Return (Form 1040) – Most states require a copy

Keep track of income earned both in and outside the state (for multi-state filers).

Step 3: Calculate Your State Taxable Income

Each state uses its own formula to determine taxable income. Most begin with your federal Adjusted Gross Income (AGI), but there may be adjustments:

1. Start with Federal AGI

Use the AGI from your IRS Form 1040 as a starting point.

2. Apply State Modifications

Depending on the state, you may need to:

- Add back certain federal deductions (e.g., state/local tax deductions disallowed at state level)

- Subtract state-specific deductions (e.g., college savings plan contributions, health insurance premiums)

- Adjust for tax-exempt income (e.g., municipal bond interest, Social Security)

3. Apply Standard or Itemized Deductions

- Some states offer their own standard deduction and personal exemptions.

- Others allow itemized deductions, either matching or differing from federal Schedule A.

4. Calculate State Taxable Income

Once all additions, subtractions, and deductions are considered, you arrive at your state taxable income.

Step 4: Determine Your Tax Liability

States use either progressive tax brackets or flat tax rates:

- Progressive Tax: Tax rate increases with income (e.g., California, New York)

- Flat Tax: One fixed rate regardless of income (e.g., Colorado, Illinois)

Multiply your taxable income by the applicable rate(s) to compute your base tax.

Credits and Prepayments

Then subtract:

- Withholding payments (from W-2s or 1099s)

- Estimated tax payments

- Refundable credits (e.g., earned income credits, education credits)

Step 5: Choose a Filing Method

You can file your state return using:

- Official state e-file portals (found on your state’s department of revenue website)

- Commercial tax software (e.g., TurboTax, H&R Block, TaxAct)

- Tax professionals (CPAs or enrolled agents)

Some states mandate e-filing if income exceeds certain thresholds.

Step 6: Submit the Return and Pay Any Balance Due

You can pay taxes owed through:

- Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT)

- Credit or debit card (may involve service fees)

- Check or money order (paper filers only)

Ensure your payment is submitted by the state’s due date (usually April 15, but varies).

Step 7: Retain Copies of Your Return

Keep a record of:

- Completed state return

- Federal return used as a base

- All W-2s, 1099s, and supporting documents

- Confirmation receipts for e-filing and payment

States can audit your return for several years after filing.

Tips for Multi-State Filers

- File a nonresident return in the state where you earned income but don’t live.

- File a resident return in your home state, but claim a credit for taxes paid to other states.

- Some states have reciprocal agreements that eliminate double taxation (e.g., between NJ and PA).

Penalties and Interest for Non-Compliance

Failing to file or pay state taxes on time can lead to financial consequences:

- Late Filing Penalty: Typically assessed at 5% of the unpaid tax per month, up to a maximum of 25%.

- Late Payment Penalty: 0.5% to 1% per month on the unpaid balance.

- Interest Charges: Accrues daily; varies by state based on prevailing interest rates.

Examples:

- California: 5% per month filing penalty, 0.5% late payment penalty, 7% annual interest.

- New York: Imposes a 5% monthly penalty for late filing, a 0.5% monthly penalty for late payment, and charges 5% interest annually on unpaid tax balances.

Extensions and Relief Options

Most states allow taxpayers to request an extension to file—typically up to 6 months. Filing for an extension only postpones the submission of your return—it does not delay your tax payment. If you anticipate owing taxes, you should make your payment by the original deadline to prevent interest charges.

Some states offer relief for:

- First-time penalties

- Natural disasters

- Undue hardship (with proper documentation)

Calculating and filing state income taxes requires a clear understanding of your residency, income sources, and your state’s tax rules. Though each state’s requirements differ, following a structured process—starting with federal AGI and adjusting per your state’s guidance—ensures accuracy and compliance. Using software or a tax professional can further simplify multi-state filings and optimize your deductions and credits

Conclusion

Being aware of your state tax responsibilities is essential for staying compliant with the law and managing your finances effectively. From income to property taxes, each state enforces its own tax code. Whether you’re a resident, a multi-state business owner, or someone working across state lines, keeping current with state tax rules helps avoid costly penalties and ensures better financial control. Leveraging proper planning tools and professional guidance can make state tax compliance far more manageable and efficient.

Freuquently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the difference between state and federal income taxes?

Federal income taxes are imposed by the IRS and apply uniformly across the United States. State income taxes, however, are determined and administered by individual states, each with its own rates, deductions, credits, and filing procedures. Some states don’t levy any personal income tax at all.

How do I know if I need to file a state income tax return?

You must file a state tax return if:

-You’re a resident who earned income above your state’s filing threshold.

-You’re a nonresident or part-year resident who earned income from sources within the state.

Check with your state’s tax agency for exact filing requirements based on income, residency, and filing status.

What is considered taxable income at the state level?

Most states start with your federal Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) and then require modifications. Taxable income may include wages, self-employment income, capital gains, rental income, dividends, and more. Some states tax different types of income differently or exempt items like Social Security benefits.

Can I use the same deductions and credits on my state return as I do on my federal return?

Not always. While some states conform closely to federal tax law and allow similar deductions and credits, others limit or deny themSome states offer specialized tax benefits, such as deductions for contributions to 529 college savings plans or targeted tax credits designed to assist renters.

What if I worked in more than one state during the year?

You may need to file multiple state tax returns—a resident return for your home state and nonresident returns for other states where you earned income. Many states offer credits to help offset double taxation.

What if I worked in more than one state during the year?

You may need to file multiple state tax returns—a resident return for your home state and nonresident returns for other states where you earned income. Many states offer credits to help offset double taxation.

How do I file my state taxes electronically?

Most states offer free e-filing on their Department of Revenue websites. Alternatively, you can use commercial tax software or a professional tax preparer to submit your return electronically.

When are state income tax returns due?

Most states align with the federal tax deadline (April 15), but some states have their own due dates. For instance, Michigan’s filing deadline falls on April 30, while North Carolina extends it to May 15. It’s important to check your specific state’s deadline to prevent late filing penalties.

Do I need to pay state taxes even if I already paid federal taxes?

Yes. Federal and state taxes are separate obligations. Even if you receive a federal refund, you may still owe state taxes depending on your income and credits. Conversely, it’s also possible to get a refund from your state.

What if I can’t afford to pay my state taxes in full by the deadline?

Most states allow you to set up a payment plan or request an installment agreement. You’ll still owe interest, but it helps you stay in compliance and avoid harsher enforcement.

What happens if I don’t file my state tax return?

Not submitting a mandatory tax return may lead to penalties, interest charges, and potential enforcement actions by the state tax authority:

–Late filing penalties (commonly 5% per month)

–Late payment penalties

-Interest on unpaid taxes

–Loss of refund eligibility after a certain period

In some cases, continued non-compliance may trigger audits or collection actions.

11. Do we need to file a state extension if I filed a fed

Mr. Nadeem Patel is an MBA graduate with a specialization in market research, bringing a sharp analytical mindset and strong research skills to the field of taxation and finance. Known for his efficiency and attention to detail, he has successfully published research work in the United States, reflecting his commitment to data accuracy and insightful analysis. Mr. Patel contributes well-researched, reader-friendly content that bridges market insights with U.S. tax-related topics, helping users make informed financial decisions.