Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT)- Best Guide 2025

Table of Contents

Complete Guide On Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT)

The Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) for corporations is a supplemental tax mechanism intended to ensure that profitable corporations with substantial income do not avoid paying federal taxes by exploiting deductions, exemptions, and credits. While AMT was largely repealed for corporations under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017, some corporate AMT provisions were reintroduced by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022, especially for large corporations.

This guide provides a comprehensive overview of corporate AMT, its history, application, calculation, and compliance requirements, making it an essential resource for tax professionals, corporate taxpayers, and financial advisors.

What Is the Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax?

The corporate AMT is designed to establish a minimum level of tax for corporations that earn significant profits but may owe little or no tax due to tax preferences such as accelerated depreciation, tax-exempt interest, or other deductions.

The AMT ensures such corporations pay a minimum effective tax, even if their regular tax liability is low.

Evolution of the Corporate AMT: Then and Now

The Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) has undergone significant transformation over the decades, reflecting broader shifts in U.S. tax policy and corporate regulation. Originally introduced in 1969 and modified extensively in 1986, the AMT was designed to prevent large corporations from exploiting excessive deductions, credits, and loopholes to eliminate their tax liability. Under the pre-2018 system, corporations calculated a parallel tax called the Alternative Minimum Taxable Income (AMTI) and paid 20% on it if the resulting AMT exceeded their regular tax.

This dual-calculation system created complexity but served as a backstop against tax avoidance. However, with the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) in 2017, the corporate AMT was fully repealed starting in 2018, as lawmakers aimed to simplify the tax code and reduce burdens on business investment. But concerns over highly profitable corporations paying little or no tax led to its revival in a new form. T

he Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 reintroduced the concept under the name Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax (CAMT), effective from 2023, with a fundamental shift in design: instead of targeting taxable income, it imposes a 15% minimum tax on Adjusted Financial Statement Income (AFSI)—i.e., a corporation’s “book income” reported to shareholders. This evolution reflects a modern strategy to address the book-tax income gap, ensuring that the largest corporations contribute a baseline level of tax based on their true economic performance.

| Period | Status of Corporate AMT |

| Before 2018 | AMT applied to corporations with certain income preferences; 20% AMT rate on AMTI. |

| 2018–2022 | Corporate AMT repealed under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). |

| 2023–Present | New Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax (CAMT) enacted via the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). |

Understanding the New Corporate AMT (CAMT)

The Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax (CAMT), introduced under the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, marks one of the most significant changes in U.S. corporate tax law in decades. Effective for tax years beginning on or after January 1, 2023, the CAMT introduces a parallel minimum tax regime designed to ensure that America’s most profitable corporations pay at least a baseline amount of federal income tax—regardless of the deductions, credits, or tax incentives they may otherwise use to reduce their regular tax liability.

Unlike the traditional corporate income tax system, which is based on taxable income as defined by the Internal Revenue Code (IRC), the CAMT applies a 15% minimum tax on a new base: Adjusted Financial Statement Income (AFSI). AFSI is a modified version of the income corporations report to shareholders in their audited financial statements—commonly referred to as book income. These financial statements are typically prepared under U.S. GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) or IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards) and reflect a company’s real-world economic performance more accurately than taxable income, which is often reduced by legally permitted tax strategies.

The CAMT is not universal—it applies only to corporations with substantial earnings. Specifically, it targets large U.S. corporations and foreign-parented multinationals with an average AFSI of $1 billion or more over a three-year period. In addition, a lower $100 million AFSI threshold applies to certain U.S. subsidiaries of foreign-parented groups, ensuring that large global firms also fall within the scope of the rule. By design, this excludes small and medium-sized enterprises, S corporations, partnerships, and most closely held businesses from its reach.

Once a corporation meets the AFSI threshold, it must calculate its tax liability under both the regular corporate tax regime (typically 21% on taxable income) and under the CAMT (15% on AFSI). If the CAMT liability exceeds the regular tax liability, the corporation pays the excess as additional tax. This creates a floor on tax payments, particularly for corporations that might otherwise use a combination of net operating losses (NOLs), foreign tax credits, depreciation deductions, and sector-specific incentives (such as green energy credits) to reduce or eliminate their U.S. tax bill.

The policy intent behind the CAMT is to capture revenue from corporations whose tax filings under the IRC diverge significantly from their financial statement profits, especially in industries like tech, pharmaceuticals, and multinational finance. By taxing book income, the CAMT minimizes the incentive for aggressive tax planning that creates a wide book-tax gap—the disparity between profits reported to shareholders and income reported to the IRS.

This move aligns the U.S. tax code more closely with international efforts to combat base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS). It complements parallel rules like the OECD’s Global Minimum Tax framework (Pillar Two), which aims to set a 15% minimum global tax rate on large multinational enterprises. Though technically different in scope and application, the U.S. CAMT shares a similar objective: to ensure tax equity, fiscal transparency, and a level playing field across borders.

In sum, the CAMT is more than a technical tax reform—it’s a policy statement. It asserts that highly profitable corporations must contribute at least a minimum amount in federal taxes, regardless of how effective their tax planning strategies may be. For tax professionals, CFOs, and corporate compliance teams, understanding the CAMT is now essential to navigating the U.S. corporate tax landscape in 2025 and beyond.

What Is Adjusted Financial Statement Income (AFSI)?

Adjusted Financial Statement Income (AFSI) is the cornerstone of the new Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax (CAMT) regime implemented under the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. Effective from tax years beginning on or after January 1, 2023, AFSI redefines how taxable base income is measured for large corporations subject to the CAMT by shifting focus from traditional tax-return income to book income—the income reported on audited financial statements.

At its core, AFSI represents a modified version of a corporation’s net income as reported in its financial statements, typically prepared in accordance with U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) or International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). These statements are submitted to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) or other regulatory agencies and are used to inform shareholders, investors, and the public about a company’s financial performance. For purposes of CAMT, this reported income is treated as a more accurate reflection of a corporation’s economic reality than taxable income calculated under the Internal Revenue Code, which may be heavily influenced by deductions, credits, deferrals, and timing differences.

However, AFSI is not identical to book income. It undergoes a series of mandatory adjustments to better align it with tax policy objectives. These include:

- Consolidation Adjustments: Income must be aggregated across all members of the corporation’s financial reporting group, even if those entities are not part of the U.S. tax consolidation group.

- Foreign Income Adjustments: AFSI includes income from controlled foreign corporations (CFCs), which is typically not consolidated under U.S. GAAP. Adjustments are made for global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI) and subpart F income.

- Tax-Free Reorganizations: Any gain or loss that is excluded from income due to tax-free merger or acquisition treatment under the Code must be added back.

- Depreciation Differences: Certain depreciation expenses claimed under tax law must be recalculated to reflect financial reporting rules, and the difference is added or subtracted accordingly.

- Tax Credit Adjustments: Refundable tax credits are added back to AFSI, while some nonrefundable credits reduce the CAMT liability rather than AFSI itself.

AFSI is calculated on a group-wide basis, including both U.S. entities and foreign subsidiaries if their financials are consolidated in the same audited report. For foreign-parented multinational groups, special rules apply to ensure that U.S. subsidiaries are not excluded from the CAMT threshold analysis. These adjustments prevent companies from minimizing their AFSI by artificially segregating high-profit entities or shifting income offshore.

Importantly, a corporation is subject to CAMT only if its average annual AFSI exceeds $1 billion over a three-tax-year period. For U.S. subsidiaries of foreign-parented multinational groups, the threshold is $100 million in U.S. AFSI, averaged over the same period. Once a corporation crosses the threshold, it must compute both its regular tax and its CAMT liability and pay the higher of the two.

AFSI Adjustments Include:

- Depreciation differences between financial reporting and tax reporting

- Tax-exempt interest income (e.g., municipal bonds)

- Income or loss from partnerships

- Foreign income and taxes

- Related-party adjustments for intercompany transactions

- Net operating loss (NOL) limitations as per AMT rules

In summary, AFSI is a hybrid metric—rooted in financial accounting principles but customized by statute to ensure fairness, neutrality, and comprehensiveness in applying the 15% corporate minimum tax. For large corporations, understanding how to compute AFSI is essential, as it directly determines whether the CAMT applies and how much must be paid. As a result, AFSI has become a critical component of tax planning, accounting, and compliance in the post-2023 corporate tax environment.

Step-by-Step Calculation of Corporate AMT (CAMT)

The Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax (CAMT), introduced by the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 and effective from 2023, applies a 15% minimum tax on Adjusted Financial Statement Income (AFSI) for large corporations. CAMT operates parallel to the regular corporate income tax system. Corporations must compute both and pay the greater of the two.

Here is a step-by-step guide to calculating CAMT:

Step 1: Determine Applicability – Does CAMT Apply?

Before calculating the CAMT liability, determine if the corporation is subject to CAMT:

- AFSI Threshold Test:

- U.S. corporations: Average AFSI ≥ $1 billion over the prior 3 tax years

- U.S. subsidiaries of foreign-parented groups: Average U.S. AFSI ≥ $100 million

If the threshold is not met, the corporation is not subject to CAMT.

Step 2: Calculate Adjusted Financial Statement Income (AFSI)

AFSI is the foundation of the CAMT and is generally based on book income (from audited financial statements), with required adjustments.

AFSI = Net Book Income (Financial Statement Income)

- Consolidation Adjustments

- Foreign Income (CFCs, GILTI, subpart F)

± Depreciation Adjustments - Tax-Free Reorganization Gains

- Certain Credit Addbacks

± Other Statutory Adjustments**

Ensure you consolidate income across all members of the financial reporting group (GAAP/IFRS consolidated entities), even if they’re not in the same U.S. tax group.

Step 3: Compute the Base CAMT Liability

Once AFSI is calculated, apply the 15% CAMT rate:

CAMT Base Liability = 15% × AFSI

Step 4: Apply CAMT Foreign Tax Credit (FTC)

To avoid double taxation on foreign income, the CAMT allows a limited foreign tax credit (FTC). This credit is based on foreign income taxes paid that are related to AFSI.

Adjusted CAMT = CAMT Base Liability – CAMT FTC

Note: The CAMT FTC differs from the regular tax FTC and is subject to its own limits.

Step 5: Compare CAMT to Regular Tax Liability

Now, calculate the corporation’s regular tax liability (typically 21% of taxable income minus credits). Compare the two:

- If CAMT > Regular Tax, the corporation pays CAMT.

- If Regular Tax ≥ CAMT, the corporation pays Regular Tax and no CAMT is due.

Step 6: Pay the Excess as CAMT Liability

If CAMT exceeds the regular tax, the difference is the CAMT liability that must be paid:

CAMT Payable = CAMT – Regular Tax Liability

This amount is reported and paid as an additional federal income tax.

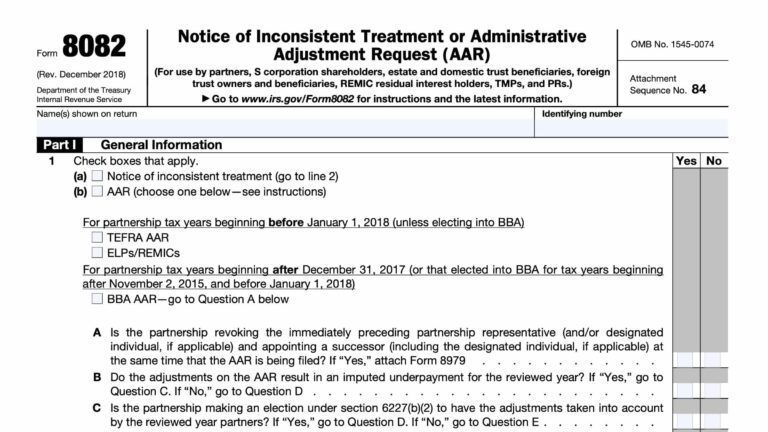

Step 7: Report on IRS Form 1120 and CAMT Schedules

Corporations subject to CAMT must file:

- Form 1120 (U.S. Corporation Income Tax Return)

- New CAMT-specific schedules (expected to include AFSI computation, threshold tests, and CAMT liability breakdowns)

Proper disclosure, reconciliation to book income, and recordkeeping are essential for compliance.

Example: CAMT Calculation at a Glance

| Description | Amount (USD) |

| Net Book Income (from audited financials) | $2,000,000,000 |

| AFSI Adjustments (net) | +$100,000,000 |

| Total AFSI | $2,100,000,000 |

| CAMT Base (15%) | $315,000,000 |

| CAMT Foreign Tax Credit | –$25,000,000 |

| Net CAMT | $290,000,000 |

| Regular Corporate Tax (21% of taxable income) | $250,000,000 |

| CAMT Liability Payable | $40,000,000 |

Who Is Subject to the Corporate AMT (CAMT)

The Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax (CAMT) is specifically designed to target the largest and most profitable corporations operating in the United States. Enacted under the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, the CAMT became effective for tax years beginning on or after January 1, 2023. Unlike the traditional corporate income tax system that applies broadly, the CAMT only applies to a narrow group of high-income corporations based on a new income metric: Adjusted Financial Statement Income (AFSI).

Here’s a detailed breakdown of who is subject to the CAMT:

1. Large U.S. Corporations with High AFSI

A corporation is subject to the CAMT if it meets the following conditions:

- It is a C corporation or a member of a C corporation group.

- It has an average AFSI of $1 billion or more over the three preceding tax years.

AFSI is calculated on a consolidated basis, meaning it includes all entities consolidated in the corporation’s audited financial statements, not just entities included in the U.S. consolidated tax group. This prevents corporations from using affiliates to shift profits or avoid reaching the threshold.

2. Foreign-Owned U.S. Subsidiaries with Significant U.S. Income

Special rules apply to U.S. corporations owned by foreign-parented multinational groups. These entities are subject to CAMT if:

- The entire multinational group has average AFSI of $1 billion or more over the previous three years and

- The U.S. subgroup has average AFSI of $100 million or more over the same period.

This rule ensures that foreign-parented firms conducting significant business in the U.S. do not escape CAMT liability by isolating U.S. earnings within subsidiaries.

3. Corporations Involved in Tax-Free Reorganizations or Large M&A Activity

In certain cases, corporations undergoing mergers, acquisitions, or tax-free reorganizations may become subject to CAMT even if they didn’t previously meet the threshold. That’s because:

- The AFSI of predecessor and successor entities may be aggregated under continuity rules.

- CAMT threshold testing is done based on combined AFSI histories.

This ensures that CAMT cannot be avoided through strategic entity restructuring.

4. Exceptions – Who Is Not Subject to CAMT

CAMT does not apply to the following:

- S corporations

- Partnerships and LLCs taxed as partnerships

- Tax-exempt organizations

- Small and mid-size C corporations with average AFSI under $1 billion

- Foreign corporations not engaged in U.S. business unless part of a qualifying U.S. subsidiary group

Important Notes on Threshold Testing

- The $1 billion AFSI threshold is calculated across all related entities, regardless of where they are incorporated.

- Financial statements used for the AFSI calculation must be audited and prepared in accordance with GAAP or IFRS.

- Corporations must test annually to determine if they cross the CAMT threshold in any given year.

The CAMT aims to ensure that highly profitable corporations contribute a minimum level of tax, even if their regular tax liability is significantly reduced through deductions, credits, or cross-border structuring. It directly responds to public concern over corporations reporting billions in financial statement income while paying little or no federal tax.

Exempt Entities Under the Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax (CAMT)

While the Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax (CAMT) was designed to ensure that highly profitable corporations pay a minimum level of federal tax, it does not apply universally. In fact, the law exempts a broad category of entities—either because they do not meet the income threshold, or because of their special tax classification under U.S. law.

Below is a breakdown of the entities that are generally exempt from CAMT requirements:

1. S Corporations

S corporations are pass-through entities for federal tax purposes. This means income, deductions, and credits pass through to the shareholders and are reported on individual tax returns. Because S corporations do not pay corporate income tax at the entity level, they are excluded from CAMT by design.

2. Partnerships and LLCs Taxed as Partnerships

Like S corporations, partnerships and limited liability companies (LLCs) that elect to be taxed as partnerships are not subject to federal income tax at the entity level. The tax burden is carried by the partners or members individually. Thus, CAMT does not apply to partnerships or LLCs unless they elect to be taxed as C corporations.

3. Tax-Exempt Organizations

Entities recognized as tax-exempt under Section 501(a) of the Internal Revenue Code—such as charities, nonprofit organizations, and educational institutions—are not subject to CAMT on their exempt function income. However, income from unrelated business activities (UBTI) may still be subject to regular tax rules and could trigger special considerations in limited cases, but CAMT generally does not apply.

4. Small and Medium-Sized C Corporations

C corporations are subject to CAMT only if their average Adjusted Financial Statement Income (AFSI) exceeds the statutory threshold:

- $1 billion AFSI (three-year average) for U.S. corporations

- $100 million U.S. AFSI (three-year average) for U.S. subsidiaries of foreign-parented groups

If a corporation does not meet the applicable AFSI threshold, it is not subject to CAMT, even if it is a C corporation. This provides a de facto exemption for the vast majority of small and mid-sized businesses.

5. Foreign Corporations Without U.S. Nexus

Foreign corporations that do not engage in a U.S. trade or business, and that do not have a permanent establishment or substantial U.S. subsidiary presence, are not subject to CAMT. However, foreign-parented multinational groups with U.S. subsidiaries must closely monitor the $100 million U.S. AFSI threshold.

Summary Table: CAMT Exempt Entities

| Entity Type | CAMT Status | Notes |

| S Corporation | Exempt | Pass-through; taxed at shareholder level |

| Partnership or LLC (partnership election) | Exempt | Taxed at partner/member level |

| 501(c)(3) Tax-Exempt Nonprofit | Exempt | Unless generating UBTI |

| Small/Mid-size C Corporation | Exempt | If AFSI < $1B |

| U.S. Subsidiary of Foreign Parent | Exempt if U.S. AFSI < $100M | Subject if AFSI thresholds met |

| Foreign Corporation (no U.S. nexus) | Exempt | Unless engaged in U.S. business |

The CAMT was crafted to narrowly target ultra-large corporations with significant book income. Most businesses in the U.S. fall outside its scope—either because they don’t meet the high-income thresholds or because their entity type is excluded. However, tax professionals must still monitor AFSI and ownership structures annually to confirm CAMT status.

Corporate AMT vs. Regular Tax: Key Differences

The Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax (CAMT), introduced by the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, represents a significant shift in how large corporations may calculate their tax liabilities. While the regular corporate income tax remains the standard tax mechanism under the Internal Revenue Code, the CAMT applies a parallel system—triggered only under specific conditions.

Below is a detailed comparison of Corporate AMT vs. Regular Corporate Tax, highlighting the key differences in base, calculation, applicability, and compliance.

1. Income Base

One of the most fundamental differences between AMT and the regular corporate tax lies in the type of income used to calculate tax liability.

- Regular Corporate Tax is based on taxable income as defined under the Internal Revenue Code (IRC). This figure reflects income after applying tax deductions, credits, and adjustments specific to federal tax law.

- Corporate AMT, on the other hand, is based on Adjusted Financial Statement Income (AFSI)—a modified version of a corporation’s audited book income. This income figure is derived from Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) or International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), and then adjusted for specific tax-related items.

Key Insight: While regular tax focuses on tax-optimized income, CAMT targets the true economic earnings shown on a corporation’s financial statements.

2. Tax Calculation Method

The method used to calculate the final tax liability under each system is also notably different:

- Regular Corporate Tax is computed by applying the flat 21% tax rate to taxable income. Corporations can significantly reduce their liability using net operating losses (NOLs), business credits, accelerated depreciation, and other tax incentives.

- Corporate AMT is calculated by applying a 15% minimum tax rate to the AFSI. The goal is to ensure that profitable corporations pay at least a baseline level of tax, even if they are able to reduce their regular tax liability through deductions or credits.

In practice, corporations compute their tax under both systems. If the CAMT liability exceeds the regular tax liability, the corporation pays the higher CAMT amount.

3. Applicability Thresholds

The regular corporate tax applies to all U.S. C corporations, regardless of size or income. It’s the default tax regime for domestic corporate entities.

In contrast, the CAMT applies only to corporations that meet specific income thresholds:

- Domestic C corporations with a 3-year average AFSI of $1 billion or more

- U.S. subsidiaries of foreign-parented multinational groups with a U.S. AFSI of $100 million or more, and groupwide AFSI of $1 billion

This makes CAMT a targeted tax, focused primarily on large multinational enterprises and corporations with significant financial book profits.

Note: Partnerships, S corporations, and tax-exempt entities are not subject to CAMT.

4. Compliance and Reporting Requirements

The compliance burden also differs significantly between the two tax systems:

- Regular Tax Filing involves Form 1120, along with supporting schedules like Schedule M-3 to reconcile book and tax differences. Most corporations are already familiar with these requirements.

- CAMT Compliance introduces new, additional reporting obligations. Corporations subject to CAMT must calculate and disclose their AFSI, book-to-tax adjustments, CAMT foreign tax credits, and CAMT net operating losses (NOLs). These are reported on new CAMT-specific schedules designed by the IRS.

The need to reconcile financial statement income with tax liabilities also places a greater emphasis on coordination between accounting and tax departments, especially for corporations using complex structures or reporting under international accounting standards.

Summary: AMT vs. Regular Corporate Tax at a Glance

| Category | Regular Corporate Tax | Corporate AMT (CAMT) |

| Income Base | Taxable income (IRC-defined) | Adjusted Financial Statement Income (AFSI) |

| Rate | 21% flat | 15% minimum tax |

| Threshold | Applies to all C corporations | Only to corporations with AFSI ≥ $1B (or $100M for U.S. subs) |

| Credits | Broad use of business and foreign tax credits | Limited credits; separate CAMT FTC rules |

| NOL Use | Up to 80% of taxable income | Only CAMT-specific NOLs from 2023 onward |

| Compliance | Standard IRS Form 1120 | Additional CAMT schedules and AFSI calculations |

| Exemptions | None (unless non-taxable entity) | Exempts pass-throughs, nonprofits, small C corps |

The Corporate AMT and Regular Corporate Tax represent two parallel systems—one focusing on tax-defined income, and the other targeting financial statement profits. While most corporations only need to worry about the regular system, those approaching or exceeding the AFSI threshold must carefully monitor their financials to avoid compliance issues and unexpected tax liabilities. CAMT isn’t just a tax—it’s a strategic accounting consideration for the largest U.S. and multinational corporations.

Corporate AMT: Forms, Reporting & Compliance Requirements

With the introduction of the Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax (CAMT) under the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, large corporations face a new layer of tax compliance. CAMT is not a separate tax system but a parallel minimum tax regime that overlays the regular corporate tax, requiring corporations to calculate and report tax liabilities using both systems.

For corporations subject to CAMT, understanding the forms, disclosures, recordkeeping, and compliance requirements is crucial for accurate reporting and IRS compliance.

1. Key IRS Forms for CAMT Reporting

Corporations must file Form 1120 (U.S. Corporation Income Tax Return) as usual. However, CAMT adds new reporting schedules to supplement the standard return:

Form 1120 (Core Return)

- The standard corporate tax return remains the primary filing document.

- Corporations subject to CAMT must still complete this form to report regular taxable income, credits, and standard tax liability.

CAMT-Specific Schedules and Draft Forms (IRS Proposed)

The IRS has proposed new schedules and updates to accommodate CAMT compliance. These may evolve annually, but currently include:

- Schedule A – AFSI Reconciliation

Reconciles Adjusted Financial Statement Income (AFSI) to book income and tax income. - Schedule B – CAMT Liability Calculation

Details the step-by-step computation of the CAMT liability, including applicable credits and adjustments. - Schedule C – CAMT Foreign Tax Credit (CAMT FTC)

Computes allowable CAMT-specific FTC, separate from the regular foreign tax credit under IRC §901. - Schedule D – CAMT Net Operating Loss (NOL) Limitation

Tracks and limits the use of CAMT NOLs, which differ from regular NOLs.

2. AFSI Reporting and Documentation

The cornerstone of CAMT compliance is accurate reporting of Adjusted Financial Statement Income (AFSI). Corporations must:

- Use audited financial statements prepared under GAAP or IFRS.

- Identify and report adjustments required under IRC §56A (e.g., depreciation differences, income inclusion/exclusion items).

- Maintain supporting documentation for all AFSI components, adjustments, and thresholds.

- Report average AFSI over three tax years to determine applicability thresholds (e.g., $1 billion test).

3. Threshold Testing and Annual Monitoring

Corporations must annually test whether they meet the CAMT applicability thresholds:

- Domestic corporations: $1 billion average AFSI (over 3 years).

- Foreign-parented U.S. groups: $100 million average AFSI (U.S. side only) + $1 billion global AFSI.

Even corporations not currently subject to CAMT must monitor these thresholds each year and maintain documentation in case of IRS inquiry.

4. Foreign Tax Credit (FTC) Compliance

Unlike the regular FTC under IRC §901, CAMT has its own limited CAMT FTC rules:

- Only direct foreign income taxes are creditable.

- No carryover or carryback is allowed.

- Must be separately calculated and applied only against the CAMT liability—not the regular tax.

5. CAMT Net Operating Loss (NOL) Tracking

CAMT has a distinct NOL regime:

- Only CAMT NOLs generated after 2022 are permitted.

- Limited to 80% of AFSI in future CAMT calculations.

- Must be tracked separately from regular NOLs on corporate records and in CAMT schedules.

6. Recordkeeping and Audit Readiness

Given the complexity of AFSI and the CAMT regime, corporations must maintain detailed records of:

- Book-to-tax adjustments

- Financial statement data (GAAP or IFRS)

- AFSI computations and thresholds

- Credits and loss carryforwards

- Legal entity structure and ownership changes

IRS audits may scrutinize AFSI adjustments, especially for multinational corporations with complex structures or material differences between book and taxable income.

7. Penalties for Noncompliance

Failure to comply with CAMT reporting obligations may result in:

- Accuracy-related penalties under IRC §6662

- Substantial understatement penalties

- Failure-to-file or failure-to-pay penalties if CAMT is owed but not reported or paid

- Potential audit exposure and adjustments

Proactive compliance and thorough documentation are key to mitigating risk.

CAMT represents one of the most complex additions to corporate tax reporting in decades. It demands coordination between accounting and tax teams, robust systems to track book income, and continuous monitoring of thresholds and financial disclosures. Corporations nearing the $1 billion AFSI mark—or U.S. subsidiaries of foreign groups nearing $100 million—must prepare early and ensure that compliance procedures are built into their year-end tax workflows.

Are There AMT Credits or Carryforwards Under the New Corporate AMT?

The CAMT (Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax), introduced by the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, differs significantly from the repealed pre-TCJA AMT regime in both structure and credit treatment. While older AMT systems allowed corporations to accumulate and apply AMT credit carryforwards to offset future regular tax, the new CAMT regime does not provide a similar refundable credit mechanism.

However, there are two key forms of tax relief available under CAMT:

- Use of CAMT Net Operating Losses (NOLs)

- CAMT Foreign Tax Credit (CAMT FTC)

Let’s break them down:

1. No Traditional AMT Credit Carryforward

Under the prior AMT rules (before 2018), corporations that paid AMT could claim a Minimum Tax Credit (MTC) in future years when their regular tax exceeded the AMT, effectively allowing them to recoup AMT paid in low-tax years.

This concept does not exist under the new CAMT.

There is no provision in the law for a CAMT credit carryforward to reduce future regular corporate income tax liabilities. Once a corporation pays CAMT in a tax year, that amount cannot be used as a credit in a future year.

Key Distinction: CAMT is a standalone, final tax when applicable. It does not generate future credits against regular tax.

2. CAMT Net Operating Losses (NOLs)

While CAMT does not allow credits like the old AMT, it does provide for a CAMT-specific NOL system:

- CAMT NOLs can only arise in tax years beginning after 2022.

- They are calculated based on AFSI—not taxable income.

- In any year where CAMT applies, these NOLs can be used to offset up to 80% of AFSI.

- CAMT NOLs must be tracked separately from regular NOLs and cannot be used to reduce regular tax.

Example: A corporation incurs a CAMT NOL of $200 million in 2024. In 2025, its AFSI is $300 million. It may apply up to 80% × $300M = $240 million in CAMT NOLs—but since it only has $200 million available, it uses all of it, reducing AFSI to $100 million for CAMT calculation.

3. CAMT Foreign Tax Credit (CAMT FTC)

For multinational corporations, the only true “credit” under CAMT is the CAMT Foreign Tax Credit, which differs from the regular FTC under IRC §901:

- Only direct foreign income taxes paid or accrued by the corporation are eligible.

- The CAMT FTC is limited—it can only offset CAMT liability, not regular tax.

- There is no carryforward or carryback provision for the CAMT FTC.

- The calculation of the credit follows CAMT-specific rules, and must be reported on a separate schedule.

Important Note: The regular FTC does not reduce CAMT liability. Corporations must calculate both FTCs independently.

No Cross-System Interaction

- Regular tax credits (e.g., R&D credit, general business credit) do not apply to CAMT.

- CAMT NOLs or FTCs do not apply to regular tax.

- Each system operates independently, and credits or losses are not transferrable between them.

Summary: Credits and Carryforwards Under CAMT

| Category | Allowed Under CAMT? | Notes |

| Minimum Tax Credit (like pre-2018 AMT) | No | CAMT liability is not creditable in future years |

| General Business Credits | No | Not usable to reduce CAMT liability |

| CAMT Foreign Tax Credit (CAMT FTC) | Yes | Separate from IRC §901 FTC; no carryforward |

| CAMT Net Operating Losses (NOLs) | Yes | Post-2022 only; limited to 80% of AFSI; cannot reduce regular tax |

| Regular Tax NOLs | No | Cannot reduce CAMT income or liability |

The CAMT regime was designed to prevent large corporations from avoiding tax entirely, especially those with substantial book profits but minimal regular tax liability. By disallowing traditional credits and limiting the use of losses, the system ensures a baseline level of tax based on financial statement income. While it does not offer traditional AMT credit carryforwards, taxpayers can still manage CAMT liability using CAMT NOLs and the CAMT-specific FTC—provided they’re tracked and applied correctly.

Example of CAMT

Corporation A:

- AFSI: $2 billion

- Regular taxable income: $500 million

- Regular tax liability (21%): $105 million

- CAMT liability (15% of AFSI): $300 million

AMT Due = $300M – $105M = $195M

Corporation A must pay an additional $195 million under the CAMT rules.

Key Takeaways

- The Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax (CAMT) was reinstated to ensure that high-income corporations pay a baseline federal tax.

- It applies to corporations with book income exceeding $1 billion, not based on taxable income.

- The 15% CAMT is calculated on Adjusted Financial Statement Income (AFSI).

- Affected corporations must carefully track book-tax differences and maintain rigorous reporting compliance.

FAQs on Corporate AMT

Is AMT still applicable to small and medium businesses?

No. The new corporate AMT only applies to corporations with average AFSI over $1 billion.

What is Adjusted Financial Statement Income (AFSI)?

AFSI is the corporation’s book income (GAAP/IFRS) with specific adjustments outlined in the IRA, including depreciation, tax-exempt interest, and foreign income.

Does the new AMT apply to foreign corporations?

It can, if part of a multinational group with U.S. AFSI > $100 million and global AFSI > $1 billion.